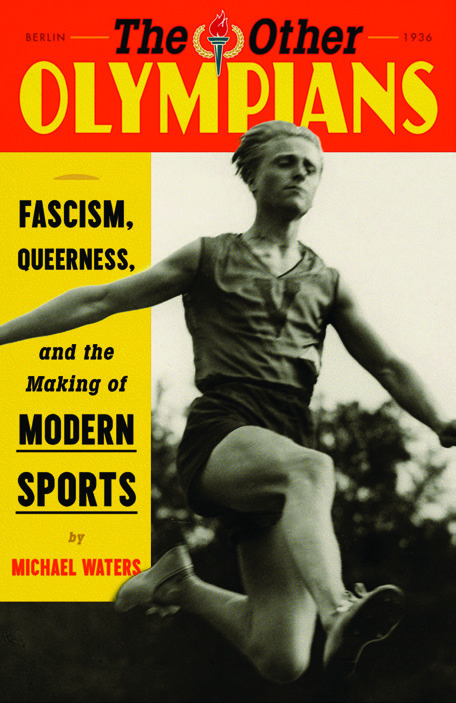

He’s going to win. It’s very apparent: much as you’re trying, hard as you’re running, as much as your lungs burn, he’s ahead by two paces. You had a good start but he’s the better athlete. You know this now. He’s gonna win this competition and you’re going to lose. But, as in the new book “The Other Olympians” by Michael Waters, there may be another outcome.

Young Zdnek Koubek avoided sports as much as possible.

Born nearly seven years before the creation of the Czechoslovakian state, he always understood that he was “different”: In school, he had a fierce reputation for fighting, but he couldn’t relate to roughand- tumble male classmates or their games. The world of girls was also baffling to him, even though, “To the world, he was a girl …”

At 8 years old, Koubek participated in his first organized sports event, a sprint he lost by “a second” that he never forgot. Seething with years-long anger, “his contempt for sports only grew” as he matured but in the fall of 1927, he had a change of heart: He’d landed a ticket to a track and field event, at which he noted how “free” it must feel to run.

“In the following months,” says Waters, “Koubek couldn’t get enough of track and field.” He began competing in — and winning — women’s events, unaware that “he wasn’t alone” in his differences.

In the early 1930s, in fact, several world-class athletes were quietly questioning their own gender; meanwhile, coaches and second- and third-place finishers cried foul over losses to “manly” women. Some athletes, assigned as female at birth, “could not evade the gender anxieties of the era.” Others lost their chance to be an Olympic competitor because of politics, and some just quit.

For other athletes with Olympic dreams, the 1936 games loomed close as they rose to celebrity status. They did so, even though Adolf Hitler and his top-ranked followers had “launched a campaign to crush Germany’s queer community.”

If a book starts out with a long list of acronyms, pay attention. Take that as a sign that you may be in for a deep look and some confusion.

Indeed, author Michael Waters seems to leave no pebble unturned in this story, which tends to drag sometimes. Readers of “The Other Olympians,” for example, may wonder why long pages are sometimes devoted to people who are never mentioned again in the narrative. Were those individuals imperative to the history here? You may never know …

And yet, there’s that depth. Waters takes his audience back to a time when heterosexuality was the absolute norm and LGBTQ people were considered to be anomalous and intriguing. The turn-around from that perception doesn’t end well, and its causation feels particularly familiar here – in more ways than one.

This is probably not anyone’s true idea of a beach read; instead, it’s timely, relevant, serious and interesting — but only if you study it fully. Don’t, and you’ll be lost. With patience, though, “The Other Olympians” is a win-win kind of read.

— The Bookworm Sez